When the National Closet Gets Too Full

By Jock O’Connell

My late Aunt Euphrasia’s daughter Philomena has long been a prescient source of market intelligence. A notoriously frugal soul, she has always shopped for household staples, along with her usual supply of “cooking” wines, at discount stores she derisively refers to as her “General Buck” stores. Back in late 2007, when signs of what ultimately came to be known as the Great Recession were still being dismissed by Wall Street firms, she began telling me about the growing number of BMWs and even Mercedes parked outside her favorite thrift shops.

Most recently, Philomena became irritated when a roll of aluminum foil at one of these down-market emporia had been marked up to $1.75, a seemingly scandalous 40% jump over the $1.25 she had paid a month earlier. Although this price hike was manifestly contrary to the gospel being preached by some officials in Washington, the checkout clerk had assured Philomena that the store manager had added the extra half-buck because of the “new tariffs”.

More likely, this was a case of a retailer preemptively seeking to cash in on headline news. Most likely, the container containing the product that set Philomena off arrived from Thailand weeks or perhaps even months before “Liberation Day”, when President Trump initially levied a 36% tariff on goods arriving from that Southeast Asian country.

Still, the episode did demonstrate that even a poorly compensated checkout clerk at a discount store understood something that certain others refuse to concede, namely that American businesses and consumers bear the major burden of tariffs.

Philomena has lately been reporting that her thrifts have taken to cluttering up the aisles with piles of unopened cartons because their stockrooms are crammed full. So far, she adds, the store managers have not asked if any employee might have space in a garage or basement to help out.

Before we get to the “please take a container home from work” stage of supply chain congestion, let’s zoom out from the kind of microeconomic observations Philomena usefully provides and consider the much larger question she posed to me last week: “What do they plan to do with all this stuff?”

It was hardly an idle query. As an avid follower of the monthly consumer sentiment surveys produced by the University of Michigan and the Conference Board as well as the Survey of Current Business from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Philomena has ample reason to expect that consumer spending, which fuels about two-thirds of America’s gross domestic product, is slowing April’s figures, released just last week, show that she was right. Despite the efforts of hoarders hedging against higher tariffs in the summer, consumer spending at retail establishments slowed to a lower than expected rate of 0.1%.

That is cause anxiety for businesses that loaded up on imported merchandise, thereby triggering a significant uptick in demand for storage space in conventional warehouses as well as in the 293 Foreign Trade Zones overseen by U.S. Customs and Border Protection, where imported goods could be temporarily shielded from import duties.

Exhibit A looks at the monthly growth rates in U.S. imports over the past five quarters. As is abundantly obvious, imports have lately spiked. Last year actually started out with a fall-off of 6.9% in consumer imports from the preceding January. Positive growth resumed in February, and the nation saw relatively modest year-over-year increases each month until late summer, when the likelihood of a second Trump term in the White House became more manifest. The convention-bending rhetoric on the subject of tariffs has been emphatic enough that, by the first quarter of this year, importers had been persuaded that the cost of sourcing products from foreign suppliers would soon jump by sizable margins.

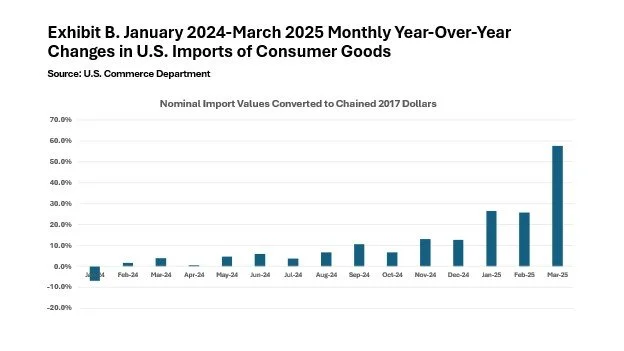

Exhibit B isolates how much imports of consumer goods have been growing in real (inflation adjusted) dollars.

Exhibit B underscores Philomena’s concerns about how retailers cope with burgeoning inventories as the nation drifts into a demand-suppressing recession. Certainly, in her estimation, retailers were not going to sell all those goods spilling out of their warehouses and stockrooms, especially if they are not eager to “eat the tariffs” by holding the line on prices. A similar problem exists for manufacturers who have imported the raw materials and components needed to meet projected levels of sales that are increasingly unlikely to materialize. Even as world-class consumers, Americans, particularly those made nervous by the prospect of layoffs, cannot consume all of what importers have imported.

So what do we look for? Businesses have numerous ways of disposing of excess inventory. Charitable donations, landfills, and incinerators are some options. But one that seems to fly under the radar is exporting merchandise that has sat untouched in storage.

Each month, the Foreign Trade Division of the U.S. Census Bureau issues the nation’s official foreign trade statistics, usually with a delay of about five weeks. Among the numbers generated are those for a category called re-exports. These are defined as goods that had previously been imported and are subsequently exported without any material change or value-added. In short, they came, they sat around in storage, and then they left without materially affecting the U.S. economy.

These re-exported goods represent a surprisingly large and growing share of America’s overall merchandise export trade, as Exhibit C reveals. The trade in re-exports has been particularly lively in the Los Angeles and San Francisco Customs Districts, which encompass the Ports of Los Angeles, Long Beach, and Oakland. Re-exports have also constituted historically high shares of all exported merchandise in the Seattle Customs District in recent years.

This is not to say that the growth of re-exports is being solely caused by excessive inventories. Rather, the increasing role of re-exports as a component of the nation’s merchandise export trade bears watching.

And that’s one thing Philomena and I will be monitoring as the U.S. economy manages its inventories if, as expected, consumption falls.

The commentary, views, and opinions expressed by Jock O’Connell are his own and do not reflect the views or positions of the Pacific Merchant Shipping Association. PMSA does not endorse, support, or make any representations regarding the content provided by any third party commentator.